Executive Summary

Collagen is undergoing a fundamental transformation from commodity biomaterial to engineered therapeutic platform. This evolution, driven by recombinant production methods, advanced composites, and precision design, positions collagen at the intersection of regenerative medicine, drug delivery, and tissue engineering. While animal-derived collagen remains clinically established, recombinant human collagen (rhColl) addresses critical limitations in batch consistency, immunogenic risk, and molecular precision. Emerging applications span wound healing, orthopedics, cardiovascular repair, and gene-enabled therapies, though most remain in preclinical or early clinical stages. For biotech innovators and translational researchers, collagen represents a versatile platform bridging molecular design, manufacturing scalability, and real-world clinical outcomes. This article synthesizes recent research to map collagen’s trajectory from passive scaffold to programmable biological construct, and examines the scientific, regulatory, and commercial challenges that will define its next decade.

1. From Structural Protein to Engineered Biomaterial

Historically, collagen’s biomedical uses focused on relatively simple wound dressings or cosmetic augmentation. Today, however, collagen-based biomaterials are being systematically designed for function, control, and biological integration – not merely as replacements, but as active drivers of regeneration and tissue remodeling.

Recent reviews summarize how collagen’s biological and mechanical properties combined with modern materials science enable diverse applications in bone, cartilage, skin, neural, dental, corneal, and urological tissue engineering. This work goes beyond describing collagen’s presence in these systems, highlighting chemical modifications, crosslinking strategies, and hybrid architectures tailored to specific regenerative needs across tissues.

Collagen is no longer just a passive matrix – it is a customizable structural framework that can be engineered to direct cellular outcomes, influence immune cell behavior through matrix mechanics and degradation kinetics, and support complex tissue reconstruction.

Disclosure: This article contains affiliate links for technical resources. I may earn a commission from qualifying purchases at no extra cost to you.

1.1 Collagen Types, Architectures, and Mechanobiology

Different collagen types play distinct roles in biomaterials design. Type I collagen, the most abundant fibrillar collagen, dominates applications in bone and skin scaffolds, while type II is more commonly associated with cartilage, and type III contributes to skin and vascular integrity. These type-specific properties are increasingly exploited in targeted tissue engineering strategies.

Collagen-based constructs are deployed in multiple architectures including fibers, films, sponges, hydrogels, decellularized matrices, and bioinks for 3D printing with pore size, fibril alignment, and stiffness strongly influencing cell infiltration, differentiation, and angiogenesis. Mechanobiology is now integral to design, as tunable stiffness and viscoelastic relaxation can be used to steer stem cell fate and tissue organization in a more predictable way.

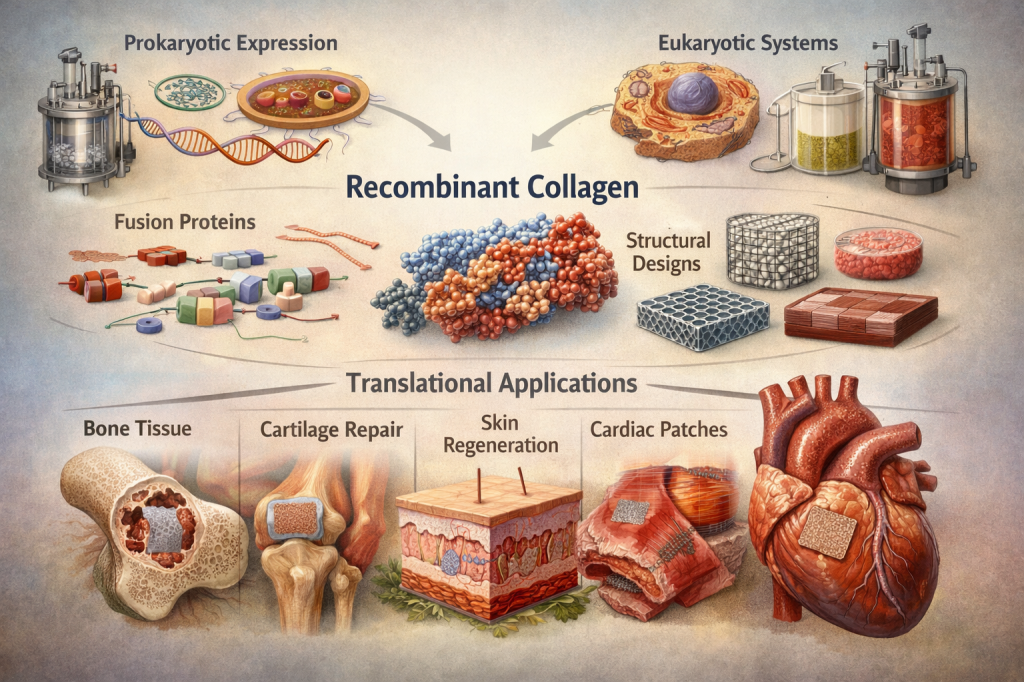

2. Recombinant Collagen: Precision, Scalability, and Clinical Potential

One of the most transformative developments in recent years is the rise of recombinant human collagen (rhColl) which is engineered at the molecular level and produced using synthetic biology platforms instead of animal extraction.

🚨Traditional (animal-derived) collagen, while remaining the clinical gold standard in many applications, faces several well-documented limitations:

• Batch-to-batch variability in composition and structure.

• Potential immunogenic risks associated with xenogeneic epitopes and telopeptides.

• Challenges in achieving high reproducibility and traceability across large-scale manufacturing.

🚨In contrast, recombinant platforms enable:

*️⃣ Defined sequences and consistent molecular architecture, allowing tunable mechanical performance and degradation kinetics.

*️⃣ Generally reduced immunogenic risk compared with animal-derived sources, subject to expression system choice and post-translational fidelity.

*️⃣ Scalable, controlled production compatible with GMP (Good Manufacturing Practice) and quality-by-design principles.

⚠️ Important technical consideration: Not all recombinant collagen products form native triple-helical structures. Many current rhColl formulations, particularly those produced in E. coli or other bacterial systems, yield truncated fragments or single-chain polypeptides that require additional processing, chemical crosslinking, or co-expression of prolyl hydroxylase enzymes to achieve stable triple-helical conformation. Full-length, triple-helical stability remains a key engineering objective, as non-helical “gelatin-like” recombinant proteins exhibit different mechanical and degradation profiles than native fibrillar collagen.

These engineered collagen systems have demonstrated comparable or improved performance across select preclinical models; for example, in skin tissue scaffolds with enhanced mechanical properties and controlled porosity relative to many traditional animal-derived sources. Comprehensive reviews indicate that recombinant collagen, guided by synthetic biology, emerging computational design approaches, and precision engineering, represents a promising avenue for how biomaterials are developed and translated into clinical use.

2.1 Emerging Clinical Evidence for Recombinant Human Collagen

Recent work has begun to move recombinant human collagen from bench to bedside, though the evidence base remains largely preclinical or early-phase clinical.

✳️ Clinical and translational studies report that recombinant human collagen formulations for wound care can accelerate wound closure, enhance dermal regeneration, and improve scar quality compared with standard dressings or animal-derived collagen in selected indications.

✳️ Recombinant collagen type III has been explored for atrophic scar modulation, with early human data suggesting improvements in scar texture and morphology linked to modulation of fibroblast function and extracellular matrix remodeling pathways.

🚨 Critical translational context: Most recombinant collagen products remain in small clinical trials or advanced preclinical evaluation. Large, randomized phase III studies are still limited, and the transition from promising preclinical outcomes to widespread clinical adoption faces hurdles including manufacturing cost, regulatory complexity, and reimbursement pathways. While the trajectory supports recombinant collagen as an emerging clinically relevant platform, robust validation in diverse patient populations and indications is ongoing.

3. Collagen in the Clinic: Regenerative and Translational Applications

Collagen has moved well beyond generic scaffolding into targeted regenerative medicine strategies across multiple organ systems.

3.1 Tissue Scaffold Engineering and Cell-Loaded Systems

Collagen remains foundational in 3D scaffolds that support cell infiltration, neovascularization, and functional tissue regeneration. Today’s constructs are engineered for biological fidelity and well-defined microenvironments, often integrating precise pore architectures, gradient stiffness, and bioactive motifs to guide cell fate.

Cell-laden collagen scaffolds, including hydrogels, sponges, and decellularized matrices seeded with mesenchymal stem cells or other progenitors, have demonstrated enhanced skin, bone, and cartilage regeneration in preclinical models. These systems underscore collagen’s role as a viable backbone for bioactive skin substitutes, bone grafts, and engineered connective tissues.

3.2 Dermal and Wound Healing Applications

Collagen-based dressings and dermal substitutes have long been employed for burns and chronic wounds, but recombinant and composite formulations are enabling more sophisticated healing responses. Recent reports describe recombinant collagen hydrogels and advanced dressings that improve angiogenesis, granulation tissue formation, and re-epithelialization in chronic and diabetic wound models, with early clinical studies suggesting faster closure and improved quality of regenerated skin.

Collagen matrices combined with growth factors or nucleic acid cargoes are also being investigated as gene-enabled wound therapies. DNA–collagen complexes have accelerated wound healing in animal ulcer models by promoting spatially controlled, matrix-bound expression of regenerative factors. However, it is important to note that clinical translation of matrix-bound gene delivery remains highly limited due to substantial regulatory scrutiny and safety validation requirements for gene-enabled scaffolds.

3.3 Orthopedics, Sports Medicine, and Musculoskeletal Repair

In orthopedics and sports medicine, collagen-based scaffolds and composites support cartilage, tendon, and ligament repair by providing osteoconductive microenvironments that promote bone formation and tendon-specific cell phenotypes. Mineralized collagen, and collagen combined with ceramics such as hydroxyapatite or bioactive glass, can enhance osteogenesis, while collagen blended with synthetic polymers (e.g., PCL [polycaprolactone], PLGA [poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)], PVA [polyvinyl alcohol]) improves mechanical strength for load-bearing applications.

3D-printed collagen-based scaffolds incorporating bone marrow–derived stromal cells have shown improved bone formation and integration in animal models, reflecting a trend toward organ-specific collagen constructs with tailored architecture and composition.

3.4 Cardiovascular Medicine and Cardiac Repair

Collagen’s role in cardiovascular tissue engineering is expanding, particularly in injectable cardiac hydrogels, vascular patches, and hemostatic materials designed to combine mechanical support with bioactivity. Collagen-containing hydrogels, often blended with polysaccharides such as chitosan and functional peptides, have improved ejection fraction, reduced scar size, and limited adverse remodeling in small and large animal models of myocardial infarction.

⚠️ Important translational caveat: While these animal model results are promising, the translational gap between preclinical success and human clinical outcomes remains significant. Materials that perform well in rodent or porcine hearts frequently fail in humans due to the substantially greater mechanical forces, inflammatory environments, and healing complexity associated with human myocardial infarction. Continued investigation is needed to determine which formulations and delivery strategies will prove durable and effective at clinical scale.

Beyond the myocardium, collagen-based vascular grafts and patches are being developed to support endothelialization and reduce thrombosis, aiming to outperform traditional synthetic grafts through better biological integration.

4. Beyond Scaffolds: Collagen for Drug Delivery and Precision Therapies

Collagen’s intrinsic degradability, porosity, and ability to bind bioactive molecules make it an attractive platform for advanced drug delivery and precision therapies.

4.1 Growth Factor and Drug-Loaded Collagen Hydrogels

Type I collagen hydrogels are being designed to deliver drugs and growth factors in controlled, spatiotemporally coordinated ways that align with tissue regeneration kinetics. Composition–structure–property relationships connect network architecture, crosslinking density, and release profiles, enabling sustained, localized delivery of angiogenic, osteogenic, or anti-inflammatory factors while simultaneously providing mechanical support.

For example, collagen hydrogels loaded with vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) or bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2) have demonstrated enhanced neovascularization and bone formation in preclinical models. Modified delivery matrices can integrate antimicrobial agents or incorporate stimuli-responsive chemistries (e.g., pH- or enzyme-sensitive linkers), blending structural support with targeted therapeutic function and reducing systemic side effects.

4.2 Gene-Enabled and Nucleic Acid–Collagen Platforms

DNA–collagen complexes and related nucleic acid–collagen hybrid systems are emerging as versatile platforms for gene delivery and cell-instructive scaffolds. By incorporating plasmids, siRNA, or aptamers directly into collagen matrices, these complexes can modulate gene expression in situ, driving enhanced angiogenesis, reduced scarring, and tissue-specific regenerative responses in preclinical models.

These platforms function as gene delivery vehicles, allowing matrix-bound nucleic acid release that enables spatial control of gene expression while maintaining the biocompatibility and biomimetic properties of collagenous extracellular matrix. Despite promising preclinical outcomes, gene-enabled collagen platforms face substantial regulatory and safety hurdles, including concerns about off-target effects, long-term expression profiles, and classification as combination biologics, that currently limit clinical adoption.

5. Composite and Functional Collagen Systems

The field is steadily moving toward composite materials that extend collagen’s utility beyond its native properties.

Common design strategies include:

• Collagen + ceramics (e.g., hydroxyapatite, bioactive glass) for bone: enhancing osteoconductivity, mineral deposition, and mechanical strength.

• Collagen + polysaccharides (e.g., chitosan, alginate, hyaluronic acid) for skin and cartilage: combining antimicrobial activity, rapid gelation, and tunable stiffness for cell-friendly environments and 3D bioprinting.

• Collagen + synthetic polymers (e.g., PCL , PLGA, PVA for musculoskeletal and load-bearing constructs: improving durability and handling while retaining biological cues for cell adhesion and remodeling.

Emerging strategies also integrate collagen with DNA and other bioactive macromolecules, creating multifunctional systems that couple structural support with targeted signaling, gene delivery, or immune modulation.

The following comparison illustrates the current state of different collagen platform approaches:

| Platform Type | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations | Maturity Level |

| Animal-derived collagen | Clinical gold standard; established supply chain; broad regulatory approval | Batch variability; immunogenic risk; traceability challenges | Mature/clinical |

| Recombinant human collagen | Defined sequence; reduced xenogeneic risk; scalable production | Triple helix stability varies by system; cost; limited phase III data | Emerging/early clinical |

| Composite collagen systems | Enhanced mechanical properties; multimodal function; tailored degradation | Complexity in formulation; regulatory classification challenges | Preclinical to early clinical |

6. Challenges, Scalability, and Future Directions

As with all frontier technologies, several challenges remain before next-generation collagen reaches its full translational impact.

6.1 Manufacturing, Quality Control, and Regulatory Pathways

Recombinant collagen production requires robust post-translational modifications, most critically proline and lysine hydroxylation, which are essential for triple-helical stability and prevent collagen from denaturing at physiological temperature. Without adequate hydroxylation, collagen melts at body temperature (~37°C/ 98°F), losing structural integrity and bioactivity.

Cost-effective scale-up and tightly controlled GMP-compliant processes are necessary to ensure consistent molecular structure and performance across production batches. Regulatory frameworks must address:

• Classification as devices, biologics, or combination products, particularly for gene-enabled or drug-loaded scaffolds.

• Comprehensive physicochemical characterization (purity, crosslinking degree, fibril organization) and biological testing (cytotoxicity, immunogenicity, degradation) for lot release.

• Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls (CMC) burden, which is substantially greater for recombinant and composite collagen products than for traditional animal-derived extracellular matrices.

These factors directly influence clinical translation, market access, and the ability to integrate collagen biomaterials into standardized therapeutic workflows.

⚠️ Reimbursement reality: For wound care and dermal matrices, reimbursement pathways and payer acceptance remain significant barriers to widespread adoption, even when clinical efficacy is demonstrated. Hospital procurement preferences, surgeon learning curves, and comparative cost-effectiveness against established treatments shape real-world uptake as much as the underlying science.

6.2 Clinical Validation and Failure Modes

While preclinical studies are prolific, large-scale clinical translation demands rigorous trials, long-term safety profiling, and harmonized regulatory standards tailored to engineered biomaterials. Failure modes such as premature degradation, scaffold contraction, calcification (particularly in cardiovascular applications), and inconsistent remodeling must be systematically understood and mitigated through iterative design and patient-specific risk assessment.

6.3 Integration with Computational Design, Systems Biology, and Digital Manufacturing

Looking forward, computational modeling, advanced simulation tools, and integrated biomanufacturing workflows will increasingly shape the future of collagen biomaterials. Potential directions include:

*️⃣ Computationally guided motif design for collagen-mimetic domains with specific receptor or growth factor binding profiles, potentially leveraging protein structure prediction and molecular modeling tools as they continue to mature for collagen-specific applications.

*️⃣ In silico modeling of collagen network mechanics, degradation, and cell–matrix interactions to guide scaffold design before fabrication.

*️⃣ Data-rich manufacturing pipelines that connect formulation parameters, structural features, and in vivo performance, supporting more robust quality-by-design strategies.

While many of these approaches remain in early development stages for collagen specifically, they represent promising avenues for creating tailored therapeutic platforms optimized for individual patient physiology and disease contexts.

7. Collagen, Commercialization, and Platform Thinking

The evolution of collagen from a commodity biomaterial to an engineered, programmable platform has implications that extend beyond the lab bench. For developers and strategists, collagen technologies increasingly sit at the intersection of:

✳️ Platform vs. product thinking: where recombinant collagen, bioinks, and composite matrices can underpin multiple indications (wound care, orthopedics, cardiovascular, aesthetics) from a common manufacturing and regulatory backbone.

✳️ Commercialization timelines and adoption: where factors such as reimbursement pathways for advanced wound dressings, clinical workflow integration, and institutional adoption patterns shape real-world uptake as much as the underlying science.

✳️ Partnering and differentiation: where control over sequence design, architectural features, and intellectual property around collagen engineering enables strategic partnerships with pharmaceutical companies, medical device firms, and contract development and manufacturing organizations (CDMOs) across both device and combination product pipelines.

Positioned this way, collagen is not just a material choice – it becomes a strategic lever connecting molecular design, manufacturing scalability, regulatory navigation, and market access.

🚨 Sustainability and cost considerations: As environmental consciousness grows in biomaterials development, recombinant collagen may offer potential advantages in supply chain traceability and reduced dependence on animal-derived materials. However, production costs for recombinant systems remain higher than traditional extraction methods in many cases, and achieving economic competitiveness at scale is an ongoing challenge that will influence commercial viability.

8. Why This Matters: Collagen’s Role in Biotechnology’s Next Wave

Collagen’s renaissance reflects a broader transformation in biotechnology:

*️⃣ From static materials to programmable biological constructs that can modulate cellular behavior, deliver therapeutics, and orchestrate multicellular regeneration.

*️⃣ From traditional implants to responsive therapeutic platforms that react to biological cues and degrade into instructive microenvironments.

*️⃣ From animal-derived extracts to engineered molecular systems, increasingly recombinant and computationally designed, with improved consistency and defined safety profiles.

For biotech innovators, translational researchers, and pharmaceutical developers, collagen represents a versatile, increasingly well-characterized platform bridging biology and engineered therapeutics. Whether in regenerative medicine, controlled drug delivery, gene-enabled therapies, or tissue fabrication, collagen’s evolutionary trajectory epitomizes how classic biological molecules can be repurposed for cutting-edge science driving impact at the intersection of innovation, medicine, and real-world outcomes.

⚠️ Important perspective: Unless otherwise noted, findings discussed throughout this article are predominantly preclinical or early-phase clinical. The path from laboratory demonstration to routine clinical use is measured in years to decades, and success will depend on continued scientific innovation, regulatory adaptation, and market forces that extend well beyond technical performance alone.

References

- Wang, Y. et al. Collagen-Based Biomaterials for Tissue Engineering. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering (2023).

- Jie, I. et al. Advancements in Clinical Utilization of Recombinant Human Collagen: An Extensive Review. Life (2025).

- He, H. et al. Recombinant Collagen in Regenerative Medicine: Expression Strategies and Translational Applications. Mater Today Bio (2025).

- Zheng, M. et al. Recent Progress on Collagen-Based Biomaterials. Advanced Healthcare Materials (2023).

- Zheng, L. et al. Recent Advances of Collagen Composite Biomaterials. Collagen and Leather (2024).

- Zuo, X. et al. Engineering Collagen-Based Biomaterials for Cardiovascular Medicine. Collagen and Leather (2024).

- Figueiredo, P. et al. Collagen Type I–Based Hydrogels: Composition–Structure–Property Relationships. npj Biomedical Innovations (2025).

- Cao, L. et al. Tissue Engineering Applications of Recombinant Human Collagen. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology (2024).

- Holme S, Richardson SM, Bella J, Pinali C. Hydrogels for Cardiac Tissue Regeneration: Current and Future Developments. Int J Mol Sci (2025).

- Jin, J. et al. Endocytosis-mediated healing: recombinant human collagen type III chain-induced wound healing for scar-free recovery. Regenerative Biomaterials (2025).

- Zhang, X. et al. Advanced Wound Healing and Scar Reduction Using a Recombinant Human Collagen Type III–Based System. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces (2024).

- He, Q. et al. Recent Advances in the Development and Application of Cell-Loaded Collagen Scaffolds. Int J Mol Sci (2025)

- Pipis, N. et al. Multifunctional DNA–Collagen Biomaterials. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering (2025).

- Reis, L. et al. Hydrogels with Integrin-Binding Angiopoietin-1–Derived Peptide for Cardiac Repair After Myocardial Infarction. Circulation: Heart Failure (2015).

- Boehler, RM. Et al. Tissue engineering tools for modulation of the immune response. Biotechniques (2011)

- Parenteau-Bareil, R. et al. Collagen-Based Biomaterials for Tissue Engineering Applications. Materials (2010).

- Shoulders, M. D. et al. Collagen Structure and Stability. Annual Review of Biochemistry (2009).

- Geeves, MA. et al. Molecular Structure of the Collagen Triple Helix. Advances in Protein Chemistry (2005).

- Verdera, H. C. et al. AAV Vector Immunogenicity in Humans. Molecular Therapy (2020).

- Braunwald, E. The War Against Heart Failure. The Lancet (2015).

- Patel, J M. et al. Bioactive Factors for Cartilage Repair and Regeneration. Acta Biomaterialia (2019).

- Teixeira Do Nascimento, A. Stimuli-Responsive Materials for Biomedical Applications. Advanced Materials (2025).

- Gorres, K. L. et al. Prolyl 4-Hydroxylase. Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (2010).

- Lee, S.L . et al. Regulatory Considerations for Approval of Generic Inhalation Drug Products. The AAPS Journal (2015).

- Fertala, A. Three Decades of Research on Recombinant Collagens. Bioengineering (2020).